Speech by Dr. Albert Winkler,

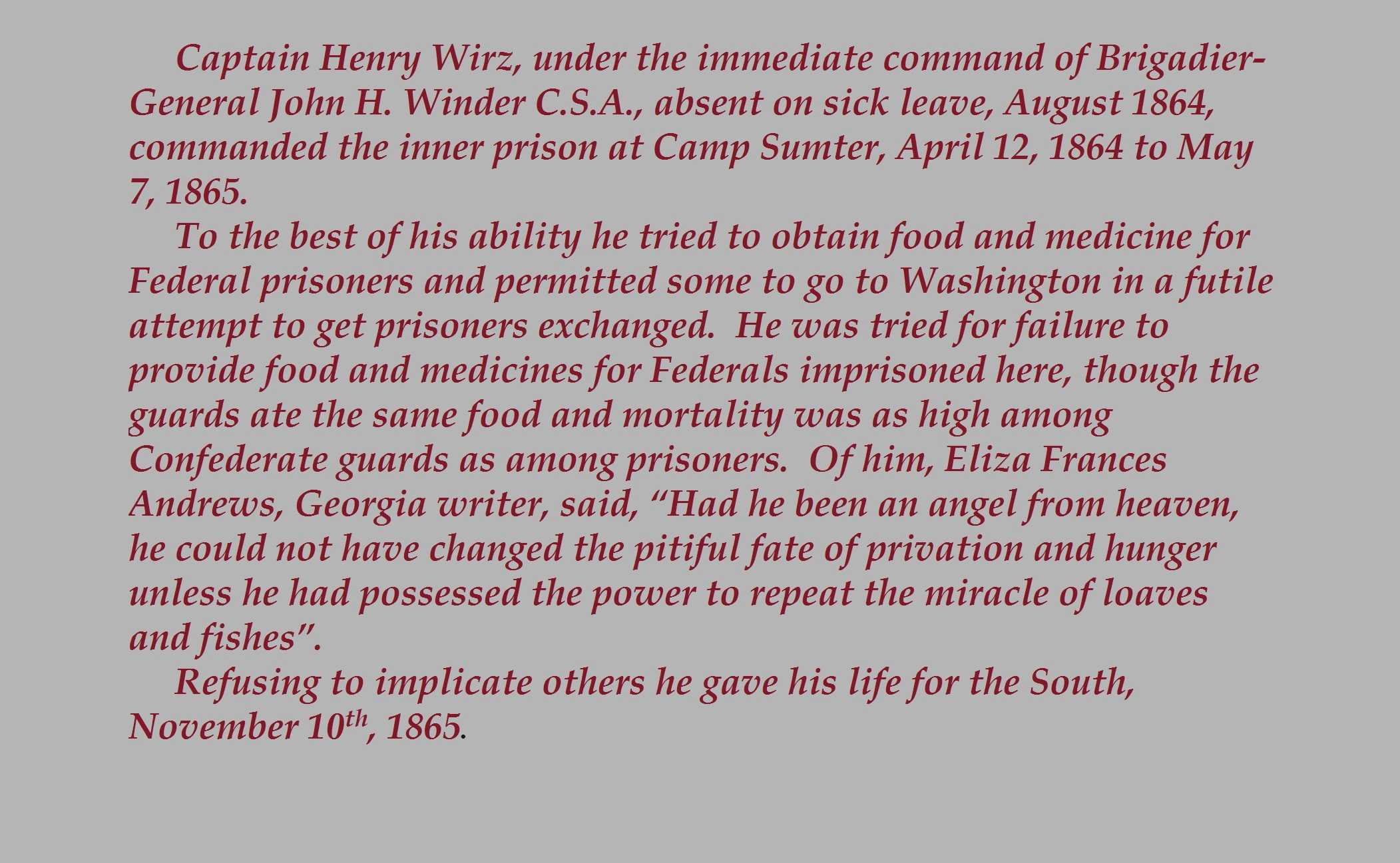

Doctor Winkler considers Capt Wirz’s greatest achievement was his refusal to spare his own life from execution if he would have implicated Jefferson Davis in some kind of conspiracy to harm Federal prisoners of war. Wirz was clearly a martyr to the cause of the Confederacy.

Let’s welcome Doctor Albert Winkler.

The trial of Henry Wirz was done by a prejudiced court. The trial of Henry Wirz was started by a

commission of 9 senior Army officers who were chosen at

Unreliable testimony.

At the trial of Henry

Wirz, the prosecution, headed by Norton P. Chipman, used the vast financial and

legal resources of the

Witnesses for the

prosecution included Confederate officers in the prison system. Lt. Colonel Alexander W. Persons commanded the

55th

Benjamin D. Dykes was

employed as a railroad agent in

“Would this day raise the standard of rebellion, if they dared to

hope for success”? There is a powerful motivator

and Chipman stated that constant vigilant was required, so Wirz had to be found

guilty, as matter of national defense. Incredibly,

Colonel Chipman spread his summation to accuse the leaders of the Confederacy,

even though they were not on trial. But,

he said they were guilty of a large number of crimes, from the treatment of

captives, to the use of guerrilla warfare, to sabotage, spreading infections, to

execution of prisoners of war, the use of landmines against soldiers and many

other highly questionable assertions. The

logic of these accusations was that since the Confederate leaders were

responsible for the war, then they were directly responsible for everything

that happened in it, either by

The verdict.

Before stating their finding on Wirz, the Commission stated the guilt of many Confederate officials. Meaning that finding these men culpable was the first and perhaps the most important aspect of the trial. “That Henry Wirz did combine, confederate and conspire with them the said Jefferson Davis, James A. Seddon, Howell Cobb, Howell Cobb, John H. Winder, Richard B. Winder, Isaiah H. White, W. S. Winder, W. Shelby Reed, R. R. Stevenson, S. P. Moore,---Kerr, James Duncan, Wesley W. Turner, Benjamin Harris, and others whose names are unknown.”

It was a very broad net almost excluding nobody at all.

“And they maliciously, traitorously, and in violation of the laws

of war, to impair and injure the health and to destroy the lives, …. the number

of 45,000 soldiers in military service of the

The soldiers mocked him as he died. The men detained to watch the execution chanting, “hang him”.

Andersonville, remember

Wirz fell as the trap door was released, but the rope failed to break his neck and writhed in agony for 20 minutes before he strangled to death. At least Federal revenge ended at that point. The sacrifice of Henry Wirz was not just for the honor of the Confederacy and refusing to implicate innocent people, such as Jefferson Davis in a plot, but his sacrifice also satiated the Union desire for more blood and there were no more executions.

Thank you very much.

Video of Dr. Winker's speech

GEORGIA MOS&B, at Andersonville GA, Nov 10th 2019

Colonel Heinrich Wirz speaks at Confederate Capt Henry Wirz Memorial

Click the link below for a PDF article on Capt. Wirz and Andersonville by Albany, Georgia Commander James W. King